What is Cancer-Related Cognitive Change?

Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI)- Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) is a term used to describe the decline in patients cognitive functions, such as perception, attention, language, thinking, learning and memory, action planning, understanding, reasoning and problem solving.

It is now well established by research studies that most individuals facing a cancer diagnosis or treatment are likely to experience changes in their thinking and ability to concentrate before, during and after cancer treatment. People often refer to changes in their cognition as “chemo brain”, however we now know that a number of other treatments and factors can cause these changes such as hormone therapy, anesthetic, negative affect or emotional distress, medication effects, and fatigue.

One study found that 30% of patients reported cognitive change prior to commencing treatment and up to 75% reported changes during their treatment.

How long these difficulties will last will depend on a number of factors including the types of treatment you received, the duration of your treatment, your current level of mental health and other psychological factors such as trauma, anxiety and depression, other side effects or symptom burden such as unmanaged pain, and medications that you may be prescribed. The research does point to this being a persistent effect of cancer treatment that can impact cancer patients from months to years after they have completed their treatment

We know that measuring the level of change in cognition can be difficult and so it can be difficult to establish or quantify the level of cognitive change you may have experienced. We also know that these changes can really reduce individuals’ quality of life, emotional well-being and interfere with a person’s ability to perform within their family or work roles and participate in social interactions.

The key areas or ways that change in cognitive functioning are identified are changes or difficulty with:

- Paying attention (focusing)

- Sustaining attention (concentration)

- Thinking quickly

- Recalling information

- Managing stimulating environments were there are multiple things competing for your attention

- Organising your thoughts

- Making decisions (i.e., even as small as what you should make for dinner)

- Planning or organising tasks

- Difficult learning new things

- Short-term memory (i.e., where you left the keys, why you walked into the room, what you were saying mid-sentence)

- Neurofatigue (brain fatigue)

What causes Cancer-Related Cognitive Change?

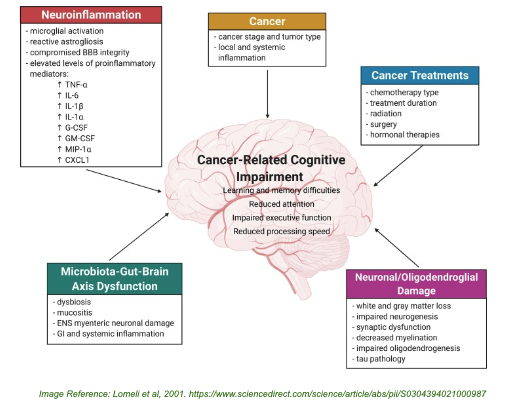

Research has been looking into the causes of cognitive change in cancer patients from about 2012 and we understand a lot more about the types of treatments and factors that can cause cognitive changes.

We have represented these below to help you identify the multiple factors that are involved. As you can see there are a lot of complex factors involved and this is a very real issue for individuals who have been through a diagnosis and treatment.

Managing Cognitive Changes

Cancer patients often ask what they can do to improve their cognition or memory after treatment has finished. Given the factors that can cause cognitive changes and impairment are multifactorial it can be helpful to speak with your healthcare professionals if you notice a change in your thinking or cognitive capacity. They may be able to address some of the factors that can cause or exacerbate cognitive changes. For example, some medications can reduce your ability to think clearly and make you less alert.

The key areas of focus of cognitive rehabilitation involve the following:

(1) Formal cognitive (brain) training- Programs such as Brain HQ or Luminosity help keep your brain active in novel ways. The research suggests to optimise cognitive improvement using these types for programs you need to engage in regular training and practice for example 30-40 min twice a week for 10 weeks (up to 40 hours)

(2) Compensatory strategies- alarms, diaries, scheduling, post-it notes, memory aides, shifting tasks/task variability in work and switching between cognitive domains-( i.e., reading, speaking. Novelty- varied stimulus- singing, reading aloud, knitting/craft coupled with a cognitively demanding task. Reading aloud if very distracted and struggling with attentional control.

(3) Attentional control training- mindfulness of sound. Attention training helps you to improve your ability to switch your attention more flexibly, equally developing the capacity for focus and to stay connected to the here and now (reduce distractibility).

(4) Managing emotions and feelings of stress, reducing self-criticism and self-frustration. Strong emotions and physical arousal can worsen cognitive performance and create secondary experiences such as reducing self-esteem, anxiety and in some situations lead to feelings of depression- (i.e., “this is not me”, “will it be like this forever”).

Speaking with a psychologist can help you also address the feelings of distress and frustration and help you identify the challenges managing your reduced capacity and address the common barriers to prioritising, planning and doing things differently.

Ways to Improve your concentration rather than your memory!

There is evidence of structural (changes in white and grey matter) and functional changes in the brain that impact connectivity and activation in parts of the brain responsible for planning, memory, decision-making and multitasking.

Research points to concentration to the key aspect of managing memory and cognitive performance. When we have difficulty establishing and maintaining attention and focus we are not able to pay sufficient attention to remember or store information to recall later and retrieving information such as words or objects can be difficult.

Concentration is the ability to stay focused on your work without letting people, feelings, thoughts, or activities get in the way. Here are a few strategies for establishing and improving concentration:

Diet and exercise have a key role in improving concentration

- Try to recognize internal distractions, such as thoughts, emotions, physical feelings, and hunger. These things can interrupt your ability to focus. Do something to reduce these internal distractions. For example, if you’re hungry, have a protein-based snack before starting a task.

- Avoid stimulants such as caffeine, sugar or salt to provide ‘energy’ to complete tasks

- Hydrate

- Maintain a stable blood sugar level

- Being active, can increase blood flow and improve oxygen levels helping reduce the sensation of ‘brain fog’ or heaviness

- There is evidence for the use of supplements such as vitamin D, magnesium and omega-3

Establishing concentration

- Be aware of external distractions. For example, give yourself permission to let your voicemail pick up calls when you’re in the middle of a task.

- Stop distracting thoughts that pop into your mind as soon as you’re aware of them. You can do this by acknowledging the thought, then consciously bringing your attention back to the task you’re working on.

- Keep a notebook or pad of paper handy. If something you need to do pops into your head in the middle of a task, write it down to get it off your mind and schedule time later in the day to do it.

- Use subvocalizing (talking under your breath) to help you maintain focus and create a auditory cue (i.e., you parked on Blue B6- repeat this aloud several times)

Increasing concentration

Figure out how long your concentration span is. To do this, write down the time you start a task (such as reading). As soon as your mind starts to drift, write down the time again. The length between your start and end times is your concentration span.

- Set aside time to concentrate. Imagine how you may feel or what you may accomplish after your task is done.

- Use a pencil or highlighter when reading. Take notes or highlight important points.

- Divide tasks into smaller, more manageable parts.

- Plan breaks according to your concentration span. Take a walk or a lunch break to help clear your head.

- If you find yourself losing focus, stand up. The physical act of standing brings your attention to the fact that you’re losing focus.

- Vary your activities. Change is often as good as taking a break.

- Learn when your concentration level is at its best. Find a time during the day when you know you won’t be interrupted and your energy level matches the particular task. Try to plan your tasks accordingly.

- Remove yourself from distractions for set periods of time to accomplish your work. Figure out what works for you, whether it’s an uncluttered desk, good lighting, or soothing music playing in the background.

- Activities such as reading aloud or sub-vocally can help maintain concentration and attention

- Attentional control training or mindfulness of sound can help you to develop your attentional control and more flexibility re-direct your attention and help reduce distractibility

- Formal Brain Training can help you vary your cognitive activity and help you practice different skills to improve your focus